Anticipation for the evening is already high, mostly in the form of will-she/won’t-she Azealia Banks performance rumors. But the upcoming exhibit is also sparking another, quieter, conversation about fashion’s relationship to feminism.

Over on Style.com, Nicole Phelps asks why New York’s top design talent is so overwhelmingly male. She points out that, in the award’s ten year history, only about 25% of the CFDA’s Swarovski Award winners were women. The numbers hold up for the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund Award: in eight years, only two women (Doo.ri Chung and Sophie Théallet) received the top prize. Phelps asks some of fashion’s most successful women to explain the gender achievement gap, and the answers boil down to: having children disrupts a woman’s career more than a man’s; female fashion editors prefer to plus-one male designers to major industry events; male designers are less concerned with fashion’s peskiest question, “Could a real woman actually wear this garment?” and more concerned with creating the kind of formally innovative, attention-grabbing clothing which appeals to the fashion press.

On the other side of the media landscape, Robin Givhan profiles Miuccia Prada for Newsweek . The Met-honored designer talks at length about her fashion philosophy, and mentions that she was reluctant to go into fashion because of her background in feminism:

“I was a feminist in the ’60s and can you imagine? The worst I could have done was to be in fashion. It was the most uncomfortable position … And I had problems for so many years; only recently I stopped. I realized that so many clever people respect fashion so much and through my job … I have an open door to any kind of field. It’s a way of investigating all the different universes: architecture, art, film.

…

I realized my job is to define—well not to define because that’s so pretentious—but to understand: What does it mean? Beauty, today, for a woman?”

Fashion so often avoids talking about feminism because, well, it’s uncomfortable: the industry does contribute, in very large part, to the culture’s unrealistic beauty standard. Fashion not only objectifies women in an abstract sense, it also concretely degrades its own foot soldiers: the harshest treatment in the industry is reserved for the young, vulnerable, and female — models, interns, assistants. The wage and achievement inequality Phelps observes at fashion’s top levels reflects structural problems of society at large, but it’s also the inevitable byproduct of the industry’s sick sexual politics. Outsiders frequently criticize fashion for hurting women, but the industry rarely reflects on its own failures. Thinking about feminism won’t kill fashion: Miuccia Prada credits it for building her career.

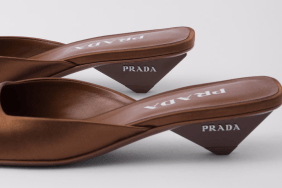

Image via IMAXtree; backstage at Prada’s Spring 2012 show